| Strange creatures - the deep ocean floor . |

|

Bizarre sea life vent communities- Tube worms: The deep-sea hot-spring environment supports abundant and bizarre sea life, including tube worms, crabs, giant clams. This hot-spring "neighborhood" is at 13¯ N along the East Pacific Rise. (Photograph by Richard A. Lutz, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey.) |

vent communities:The manipulator arm of the research submersible Alvin collecting a giant clam from the deep ocean floor. (Photograph by John M. Edmond, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.) |

vent communities: The size of deep-sea giant clams is evident from the hands of a scientist holding them |

|

vent communities: Close-up of spider crab that was observed to be eating tube worms |

geothermal vents: View of the first high-temperature vent (380 ¯C) ever seen by scientists during a dive of the deep-sea submersible Alvin on the East Pacific Rise (latitude 21¯ north) in 1979. Such geothermal vents--called smokers because they resemble chimneys--spew dark, mineral-rich, fluids heated by contact with the newly formed, still-hot oceanic crust. This photograph shows a black smoker, but smokers can also be white, grey, or clear depending on the material being ejected. |

THE DEEP-SEA FLOOR: seapig. For marine biologist, the sea pig goes under the name Scrotoplanes. They feed on things found in the mud of the deep sea floor by using the tentacles to scope it in. Sea pigs live on or underneith the surface of the bottom. |

|

Scrotplanes belong to the phylum Echinoderms, which includes other sea floor creatures such as sea stars, sea urchins and sea cucumbers. In the phylum, they are further classified as Holothuroidea, which states that they are more related to the sea-cucumbers than the other members of this phylum. Together they form large groups on the sea floor, making their way in a sludge-like fashion. Movement is generated by using long tube feet. I don''t know if these feet is what can be seen on the picture on the left, or if those feet-like thingies are just some tentacles or confusing ornaments of unknown purpose - |

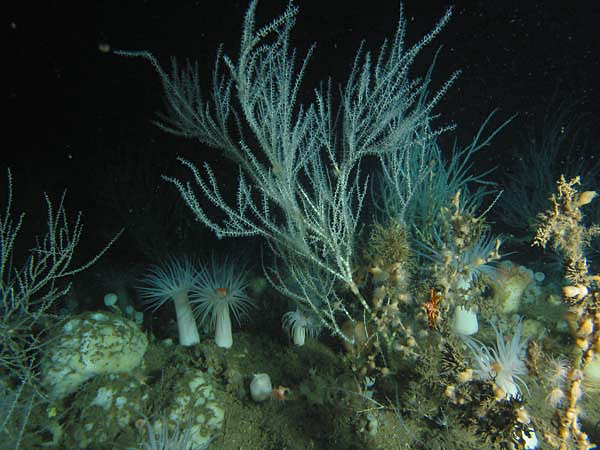

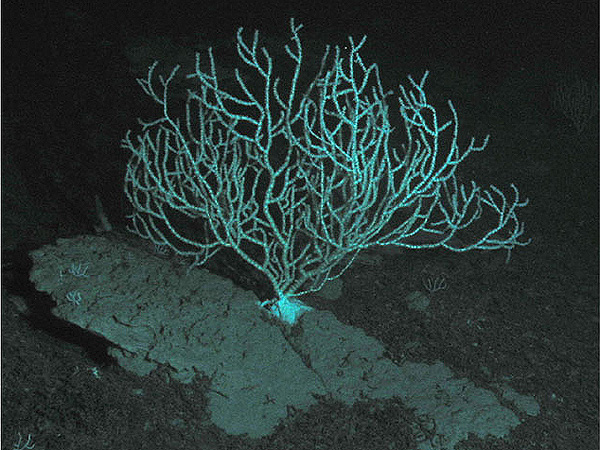

The deep-sea floor holds many beautiful scenes, such as this. Exploring how plants and animals have adapted to life this extreme environment can open doors to a greater understanding of our planet. Image captured from submersible still camera. |

This Caranchid squid, about four inches across, uses transparency to hide from potential predators. Open-water divers can more easily observe these creatures with polarizing filters. Compare the polarized and unpolarized images. |

|

short-nose greeneye fish. The submersible team collected the specimen for optical studies in the ships onboard laboratory. Image courtesy Edie Widder. |

Under white light the green lenses of this six-inch greeneye fish are still quite apparent |

This deep sea shrimp, Acanthephyra purpurea, spews bioluminescence to blind or distract a predator |

|

An example of fluorescent features observed in a deep-sea community. This basalt rock, collected at 1,700 ft, is overgrown by polychaete worms, bryozoans (violet reflection) and sponges (green fluorescence). The nature of the red fluorescent stains on the rock and the small glass sponge (lower half, center) is uncertain. |

Pillow lavas may be the world''s most common extrusive igneous formation, but they only form on the deep sea floor - Pillow lavas (or lava pillows) form when lava is erupted into cold seawater: the outer layer hardens rapidly, and the molten rock is forced to start new pillows instead of becoming a steady flow. These pillow lavas range in age from the present to about 450 million years ago, a vivid instance of the old saying that in geology, the present is the key to the past. Learn more about pillow lavas http://geology.about.com/od/structureslandforms/ig/pillowlava/ |

Whalefall after 18 months, Santa Cruz Basin, 1670m. A whale fall is defined as a dead whale sinking and transporting nutrients to the sea floor. Whales are the only marine mammals that have so far been found to be associated with similar animals to those found on hydrothermal vents and cold seeps - i.e. have associations with chemosynthetic fauna. Following the discoveries of hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, scientists have found that certain large falls of organic matter that land on the deep-sea floor can also be the basis for the development of animal communities related to vents and seeps. Researchers have suggested that these habitats could be used as stepping stones for vent and seep species to disperse between ocean basins. |

|

COLD SEEPS: Lamellibrachia tube worms. |

The deep-sea floor: Muggles |

The Deep-Sea Floor Author: Sneed B. Collard III |

|

|

the deep sea |

Sea cucumber |

|

During an expedition in the Gulf of Mexico in 2007, Natural Marine Sanctuaries captured these images of a brine channel at the base of East Flower Garden Bank. Hypersaline water flowing from under the sea floor created a concentrated brine lake and river measuring about 10 niches deepBecause of their high salinity, nothing can live in the brine but bacteria and the few other creatures that can live near it are mollusces or shrimp.. |

High Arctic sea star collected on the deep-sea floor, Canada Basin (NOAA image by Bodil Bluhm and Katrin Iken) |

scyphomedusae |

|

Acanthometra, a radiolarian with skeletal spicules of strontium sulphate, and foraminiferans from the Indian Ocean. |

Marine nematode worm. Nematodes or thread worms are one of the dominant groups in deep-sea muds. There are certainly thousands, possibly tens of thousands, of species still to be discovered. |

Foraminiferan remains from the White Cliffs of Dover, UK. The cliffs are made up of unimaginable numbers of chalky shells of long-dead marine animals. Foraminifera are very simple organisms that consist mainly of protoplasm |

|

Most starfish, whether in deep or shallow water, obtain their food from the sea bed itself. But some, like this one, Freyella elegans, photographed at a depth of 4,000m in the north Atlantic, spread their arms into the water above the bottom and catch food particles carried in the water currents |

Sea cucumber, holothuriaor holothurian Peniagone diaphana, from the deep-sea floor. Unlike most sea cucumbers, this one can swim using slow undulations of its muscular body. |

Tripod fish |

|

oneirophanta |

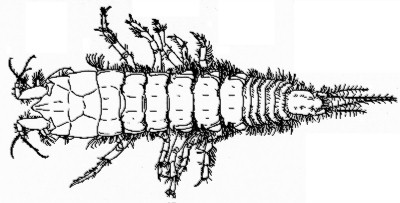

the Family Apseudidae |

The only rock observed at the Popenoe''s Coral Mounds dive site was a loosely cemented foraminiferan "ooze." A bamboo coral used this lonely outcrop as a solid base on which to live. We collected only a small portion of this rock. |

|

Vent |

Vent: Galatheid Crabs |

Vent Communities Under the Galapagos Islands |

THE DEEP-SEA FLOOR

Most of the deep-ocean floor is an area of endless sameness. It is eternally dark, almost always very cold, slightly hypersaline (to 36%0, and highly pressurized. But there are 4,500 organisms per square meters. There were 798 species recorded in 21 samples in 1980s: a blind tripid fish, abyssal bentic animals such as oneirophanta, holothurian (sea cucumber), apseudes galatheria in the Kermadec trench, oneirophanta.

Marine Zoogeography, 1974, from J.C.Briggs. the ooze.

The deep-sea floor is the oceans most uniform habitat. It is populated by a large variety of highly specialized species.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scotoplanes

http://animals.jrank.org/pages/1631/Sea-Cucumbers-Holothuroidea-SEA-PIG-Scotoplanes-globosa-SPECIES-ACCOUNTS.html

Smaller beasts

Foraminiferan remains from the White Cliffs of Dover, UK. The cliffs are made up of unimaginable numbers of chalky shells of long-dead marine animals. Foraminifera are very simple organisms that consist mainly of protoplasm.

Apart from when they are brought together by these food bonanzas, animals big enough to be seen with the naked eye are distributed fairly thinly on the deep-sea floor with perhaps one animal every 10 or 20m. But for every one of these big animals there are many thousands of tiny ones, no more than a few millimetres long and living hidden away in the abyssal mud. Many different animal groups are represented here, but just four or five groups dominate in terms of numbers.

First, at the lower end of the size range are the single-celled animals, the foraminiferans and their relatives. These are very simple organisms which feed by engulfing bacteria or other tiny pieces of organic matter into their protoplasm, and are extremely numerous. By secreting a chalky shell, or by sticking together mud particles or pieces of other animals'' shells into balls, tubes or multi-chambered little houses in which they live, these tiny animals produce a bewildering variety of strange shapes.

Acanthometra, a radiolarian with skeletal spicules of strontium sulphate, and foraminiferans from the Indian Ocean.

Another important group of single-celled animals are the Radiolaria. They have skeletons made of glass-like silica or strontium sulfate, often in radiating spicules--hence their name. Most of the 4,000 or so species are planktonic, but a few live on the bottom.

The second most abundant group, and among the smallest of the many-celled animals, are the nematodes or thread worms. Nematodes are found in all environments--marine, fresh-water and terrestrial--and may outnumber all other many-celled animals on Earth. In the deep sea they range in length from a few tenths of a millimetre to a centimetre or more, and include bacterial grazers (specialist predators that can puncture the prey''s cell membranes and suck out the internal juices), and active and deadly hunters.

Marine nematode worm. Nematodes or thread worms are one of the dominant groups in deep-sea muds. There are certainly thousands, possibly tens of thousands, of species still to be discovered.

The crustaceans are the next in importance. They include amphipod shrimps, which are related to, but much smaller than, the big scavenging amphipods, and several other groups specialised in producing tunnels or in pushing their way through the sediment by simply moving aside mud particles or other animals. Deep-sea isopods appear in a variety of forms--some resemble their terrestrial relatives, woodlice; others have a flattened form; some have long, thin, matchstick-like bodies ideal for ploughing through the sediment; others have long spindly legs well-suited for walking across the soft surface of the mud.

The most abundant of the mud-dwelling crustaceans, however, are the harpacticoid copepods, related to the dominant zooplankton group in the mid-water realm, but specialised for living in the sediment and feeding on bacteria or organic detritus.

Newly discovered polychaete worm, Sigambra sp., from the floor of the abyssal Atlantic. Though some polychaetes reach 10-20cm, most deep-sea species, like this one, are a few millimetres long.

Next come the polychaete worms which are found at all depths and include very mobile species, which crawl actively across the bottom, or even swim; and sedentary species, which live in tubes or burrows, and either forage over the sediment surface for pieces of food or catch floating particles with feather-like tentacles.

Only one other deep-sea, mud-dwelling group, the bivalve molluscs (relatives of the shallow-water clams and mussels with two shells, or valves, hinged together), approaches the polychaetes in abundance. Most deep-sea bivalves live buried in the sediment and send out feeding palps to gather pieces of food from the surface of the mud, while a few have become accomplished carnivorous hunters.

But most surprising of all, there are specialist deep-sea, wood-boring bivalves. Their environment is just about as far from a source of any wood as is possible. These bivalves will attack the hulls of sunken wooden ships, but they were around long before humans first sailed over the deep ocean. Unlikely as it seems, trees from coastal forests must fall into the sea and eventually sink into the abyss sufficiently often to make this strange lifestyle worthwhile.

VENT COMMUNITIES

Hydrothermal vents and their exotic fauna were first discovered on the GalÃpagos Rift in the Pacific as recently as 1977!! Vents are found on mid-ocean ridges and back-arc basins, which are deep-water volcanic chains. One of the most striking adaptations of vent animals is their association (symbiosis) with microogranisms that use the chemical energy found on the vent fluids for the production of organic matter.

1976 Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Riftia tube worms, chemosynthetic bacteria, , giant white clam, Calyptogena magnifica

Deep-vent communities, near black smokers and atop cold seeps, depend on chemosynthesis rather than photosynthesis for energy.

Cold seep ecosystems were found for the first time as recently as 1984 in the deep Gulf of Mexico! The animals that thrive on cold seeps are similar to those found on hydrothermal vents and also depend on the production of microorganisms that use reduced chemicals as source of energy.

Lakes

650ft beneath the waves

Deep beneath the waves, far down on the ocean floor are scenes and images often associated with the stuff of nightmares - translucent fish with wide black eyes capable of seeing in the dark, shell fish with bioluminescent skeletons and colossal squid, so huge that no one has yet to picture them. All these creatures, though bizarre, are somehow quite expected but its doubtful whether many people when asked what else they would find strange to discover at the bottom of the ocean would picture a lake.

As unlikely as it sounds there are a handful of underwater lakes and rivers boasting their own mini ecosystems.

Abyss Greek word meaning ''bottomless''. The deep part of the oceans, between about 3,000m and 6,000m deep.

Amphipods Group of shrimp-like crustaceans ranging in length from a few millimetres to more than 10 cm.

Bacteria Tiny living organisms, neither clearly plants nor animals, which have no clear nucleus like the cells of most other creatures.

Copepods One of the most important groups of planktonic crustaceans in the oceans. Most are small, just a few millimetres long, and many feed on phytoplankton cells.

Hydrothermal vents Springs of very hot, chemically-laden water gushing through the sea floor along the mid-ocean ridge system.

Species The basic unit into which scientists divide the living world. Members of a species can interbreed with one another, but not with members of another species.